Finding Joy in the Stories We Wear

Finding Joy in the Stories We Wear

This summer on Martha’s Vineyard, I found myself breathing in history as much as salt air. The island has long been a sanctuary a place where Black families, artists, and thinkers have come for generations to rest, convene, and create. On its beaches and porches, I felt our legacy in the air: the beauty of belonging layered with the serenity only the ocean can offer.

And yet, even amid this calm, I could not escape the sense of turmoil pressing in from beyond the shore. Across the country, the teaching of Black history is under attack. Our stories are being stripped from classrooms, our narratives reduced or erased. On the Vineyard, I felt the weight of this juxtaposition of protection and vulnerability, serenity and struggle. The island was both backdrop and reminder: our heritage is living, but it must also be defended.

It is in moments like these that I am reminded why storytelling matters. Why fashion, for me, has become a way to protect and preserve our legacy. Why I believe that preservation is not just an act of resistance it is a collective necessity.

Storytelling has always been the heartbeat of the Black community. It has carried us when written words were forbidden, sustained us when knowledge was deemed dangerous, and guided us when silence was forced upon us. Our ancestors knew that stories were not just memory they were survival. Reading and writing were once acts of defiance that could cost you your life. And yet, we endured.

We listened at the hems of our grandmothers’ skirts as she greased our scalps, her hands moving in rhythm with words that reminded us of where we came from. We leaned against the pickup trucks of our grandfathers or lingered near porches to catch stories carried in between pauses of tobacco smoke and laughter. In those intimate, ordinary moments, we inherited a tradition of resilience. These were not just tales they were blueprints, prayers, and warnings disguised as parables.

Today, so much of that tradition is at risk of being diluted, forgotten, or stripped away. That is why preservation is not an act of resistance it is an act of collective necessity. As Toni Morrison once reminded us, “The function of freedom is to free someone else.” Our freedom lies in protecting the truths our ancestors fought to pass down, and ensuring those truths live beyond us.

Today, the stakes remain just as high. Our oral traditions are imperiled by the speed of the digital age and by the persistent attempts to strip Black history from the public record. In this climate, the preservation of Black history is not simply resistance it is collective necessity. If we fail to hold our stories close, we risk losing more than memory. We risk losing the blueprint for freedom itself.

Fashion has long been one of the most visible sites of Black storytelling. As scholar Tanisha Ford argues in Liberated Threads, clothing has never been mere adornment it has been an instrument of politics, identity, and cultural continuity. From the church hats of the Black South to the dashikis of the Pan-African movement, our garments have been statements as much as they have been styles. Elizabeth Way, curator at The Museum at FIT, notes how Black dress practices in the early 20th century became essential tools for claiming visibility in a society structured to render Black people invisible.

The history of the “Black Ivy” is one of my favorite examples. Jason Jules’ Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style illustrates how Black men of the mid-20th century redefined preppy clothing once a symbol of exclusivity and whiteness into a language of self-determination. Wearing ivy league tweeds, loafers, and button-downs, they presented themselves with sophistication in the face of a world that insisted on calling them “boys.” Their polished appearance was not just style; it was defiance. Each jacket and tie demanded dignity. It was, as Stuart Hall might say, a negotiation of identity in the public sphere a way of re-signifying what Blackness could mean.

Garments in this tradition function as what historian Robin D. G. Kelley calls “freedom dreams” material visions of the world we are trying to build. To wear our stories is to assert our humanity, to dare joy, and to bind ourselves to a lineage of survival.

I witnessed the connection between apparel and identity long before I ever dreamed of founding Bee Blunt. My father, a Marine for 36 years, taught me that what you wear is never incidental. Watching him prepare his uniform was to witness ritual. Each starched shirt, each creased trouser, each shined boot was a lesson in discipline and dignity. Anything less was unacceptable. Shirts were always tucked. Belts always buckled. Boots polished until you could see your reflection.

But that meticulous care was not just the Marine Corps speaking it was Black culture carried forward. It was the same ethic of presentation taught to him by his mother and grandmother, who knew that appearance could shield, dignify, and even protect in a world that too often sought to diminish. In his uniform, I saw not just precision, but pride. The uniform itself became a story, a garment that communicated duty, discipline, and resilience.

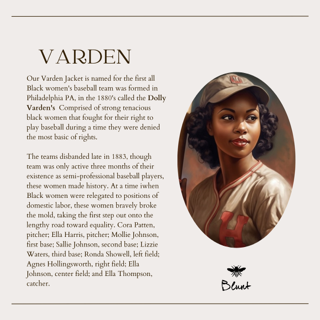

That lesson lives in my work. Fashion, for me, is not about trends but about testimony. Each garment I design for Bee Blunt is a canvas for our shared history. When I created the Inkwell Sweater, I wanted to honor Martha’s Vineyard’s storied Inkwell Beach, a gathering place for generations of Black families who claimed joy and belonging on its sands. When I designed the 1825 Sweater and New Guinea Scarf, it was to preserve Nantucket’s Black history the renamed neighborhoods, the African Meeting House, the legacy of resilience against erasure. These pieces are more than clothing. They are archives you can wear. This is how I preserve our oral tradition: in wool, in silk, in jacquard knits. My pieces are not simply clothes; they are conversation starters, cultural signifiers, and invitations to remember. They embody the continuum of Black storytelling from the porch to the runway, from whispered folktales to woven patterns.

When someone asks, “What does that flag on your sweater mean?” the garment becomes more than fabric it becomes a portal into history. A conversation starter. An act of remembrance. And perhaps most importantly, an act of joy.

What we are protecting is more than history it is joy. Too often, the story of Black life is told only through pain. But woven into every act of survival was laughter, song, improvisation, and beauty. Our ancestors, even in bondage, found ways to dance, sing, and create. To center joy in our storytelling is not to ignore the pain but to insist that resilience blooms from it.

As historian Robin D. G. Kelley writes in Freedom Dreams, Black cultural expression is not just about surviving the present but imagining a liberated future. To preserve these stories whether in books, in song, or in fabric is to insist that joy is our inheritance.

I have pride in who I am. I have pride in where I come from. The pain of the past is real, but it has only widened the capacity for joy in the future. Through the powerful work of Jenee Osterheldt at the Boston Globe, founder and creator of A Beautiful Resistance I have learned that our joy in being black is one of our most powerful tools of resistance. That joy is endangered only if we allow the triumphs that define us the dignity claimed in dress, the resilience carried in stories, the creativity stitched into every hem to be diminished.

So we find ways through music, art, design, and fashion to safeguard our legacy. The garments I create are my contribution to that continuum. They are my way of saying that our stories matter, that they will not be erased, and that beauty itself can be an act of protection.

When we preserve our stories, we preserve our future. And when we wear them with pride, we make visible the truth that has always carried us: our joy cannot be denied.

Fashion is my way of protecting legacy, sparking dialogue, and carrying the weight of history forward into beauty. It is how I honor the voices that were silenced, and the ancestors who risked everything so that I might create freely.

Our stories are our greatest inheritance. And if we are to preserve them, we must find ways through art, music, design, and everyday ritual to keep them alive. That is the work. That is the calling. And that is the joy.